Today we come to the end of our “Let’s Read!” edition. For two months, we’ve focused on the importance of improving the reading skills of Costa Rican children and youth. During this time, we’ve learned that if we don’t achieve this, our country and our democracy are in danger.

Although the challenge is complex, we’ve learned that there are ways to address this problem. Our in-depth reports, through the lens of solutions journalism, show how access to books can be improved, even with a small step like a little student library—because this scarcity is among the main reasons that children fail to achieve better reading skills. We also learned about ways to make reading more enjoyable: for example, by showing kids that their own stories are worthy of publication and celebration, when we share books that reflect their own lives.

But something else happened during these two months, behind the scenes. Katherine and I created a “Teacher’s Lounge” in our Education 506 WhatsApp community, which is open to teachers and anyone else who’s passionate about education in Costa Rica. What does that mean? Well, on several Thursday afternoons, we brewed some coffee, opened up the chat, and talked about reading.

During those meeting times in our virtual Teachers’ Lounge, we learned a lot about our community. Today, we want to share it with you.

Costa Rica needs more libraries. Lots more.

We’ve learned that the single most important step to promote reading for all, regardless of age, is access to books and the ability to choose for themselves what they want to read. what to read. We learned this from our months of reporting and reading academic and non-academic publications, and from a wide variety of interviews, and from comments on our social media. And it came through loud and clear during our Education 506 WhatsApp chats with teachers around the country.

But as we have also reported, access to books is not so simple. In Costa Rica, books are expensive, and for lower-income families, they will not be a priority. Access to reading material in schools can be one solution, but financial restrictions are present there as well.

“But in schools, using ‘books’, in my case, is something that students cannot be asked to do,” said Arturo Barrantes Mora, an English teacher at the Bataan Professional Technical College, Limón. “A book for a student in the area where we are would be from ₡5,000 to ₡9,000 (approximately $9-16). That, for more than six subjects, is impossible. So we provide other material instead of books.”

“Access to affordable books is very limited,” agreed Heather Frid Jiménez, co-founder and director of HeartSong Community of Free Learners. “I share this experience. If there is really a commitment from the government / MEP [Ministry of Public Education] to change the situation, it would be necessary to invest in public libraries and school libraries so that students do not have to buy the books, but can borrow and return them for continuous use year after year.”

However, we know that the MEP has not been able to achieve this. Only 30% of schools have a library—and those are mostly in the Greater Metropolitan Area.

One member of Education 506 took the bull by the horns and created her own library.

“I had a lot of books and I didn’t know what to do with them, so in my classroom I decided to make a corner with a ‘rent for free’ sign so that my students could take a book, read it and then return it to me,” says Yessenia Salazar, an English teacher at the Alajuelita Professional Technical College. “I have a notebook where we write down the name of the book, the student’s name and the date. They can keep it for a month, and if they need to, they can ask me for more time. (At school we don’t have a library or any other place with access to free books)”.

Erick Celiciano Matamores, an English teacher at the Santa Eduviges Academic High School and the Matapalo Professional Technical College, both in Puntarenas, also says that too much of this responsibility for access to books is placed on individual teachers and institutions.

“There are always places that throw away books or, in the best of cases, donate them,” he says. “I remember when I worked in a private school in 2012: a number of books were donated to the schools.

“Of course, it’s not just about accepting a donation, or looking for them,” continues Erick. “You have to have a plan to use them.”

Arturo says he believes that one solution is to expand the formats in which we let students read.

“Find books, ebooks, audiobooks, BookTubers, storytellers, etc… that can be part of the resources for students in an easy way to enjoy reading,” he says. “Create book clubs or podcasts with book recommendations. Encourage teachers to create projects in their schools. Hold reading time in the library. Activate library spaces to investigate and motivate reading. Bring writers to schools. Bring theater to schools. Change the chip!”

Teachers need more reading-focused spaces—informal and formal.

“Teachers must love reading. We give what we have,” says Arturo. “But you also have to motivate [teachers], support them, and listen.”

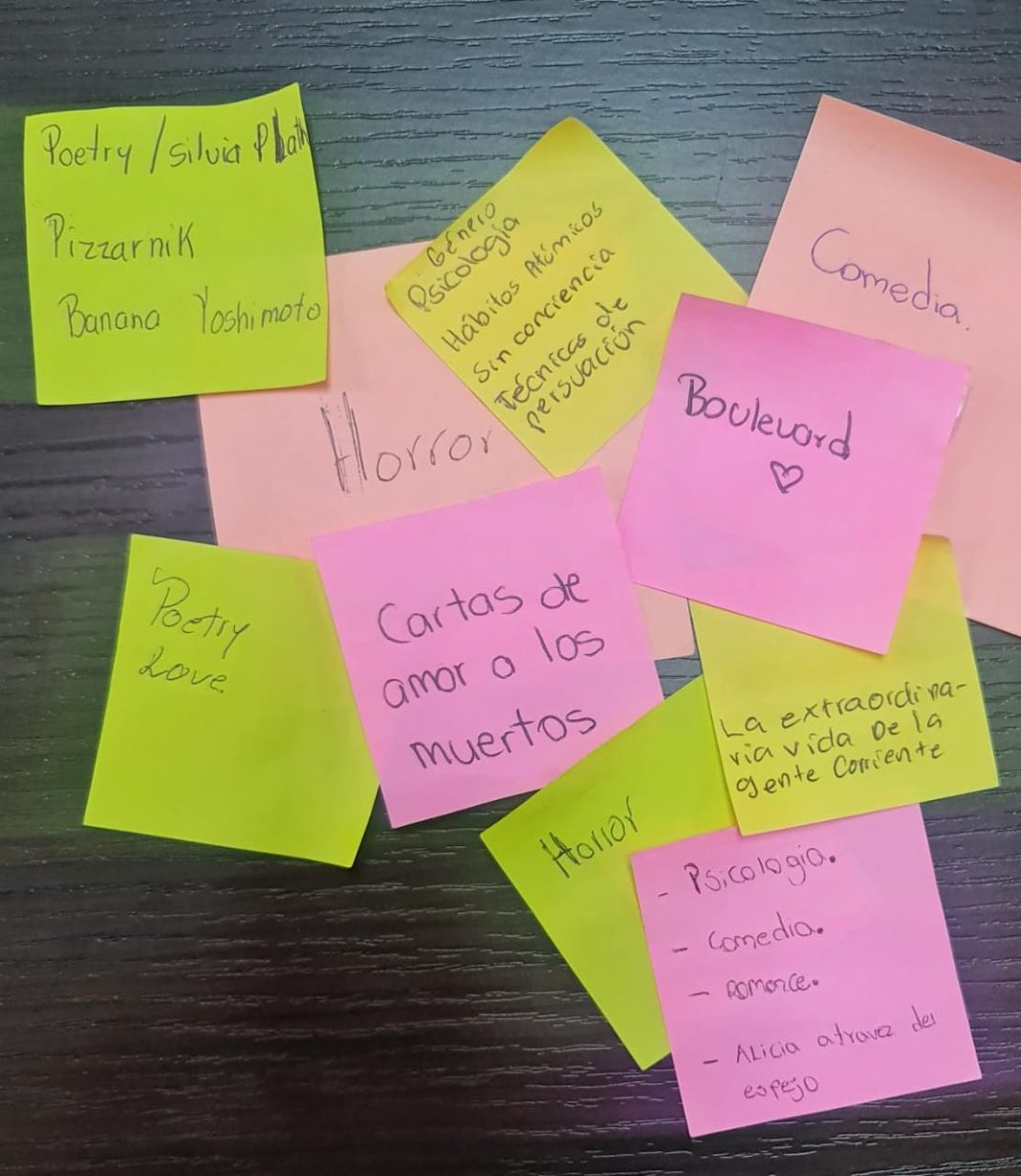

As we talked with our community about teachers’ responsibilities, Katherine threw out the idea of book clubs among teachers.

“I think it could be successful,” Yessenia replied. “In addition to reading for pleasure and enjoying good reading, we could consider books that apply to classroom work and strengthen methodologies and activities in class.”

However, the people who participated in the chat believe that much more is needed than motivational activities like this. These teachers say they need more leadership from the MEP.

“In the area of English, I think that an important resource would be creating standardized books for each school level that include what each unit of the curriculum requires,” says Karla Rodríguez Sánchez, a preschool and elementary school English teacher at Escuela Monseñor Sanabria Martínez, Atenas, Alajuela. “Make them engaging to students, and include texts that relate to student/real life interests. And once you’ve covered all levels of the national curriculum, you can think about other resources to motivate reading.”

Karla says that by giving teachers total freedom to teachers to select or create all of their own materials, the MEP has actually created greater inequalities in student progress. She says that a unified system would allow teachers to “devote a little more time to other activities and develop more skills, such as reading.”

“The problem is that they do not teach with a goal”, says Erick in that same conversation. “Everyone teaches in their own way. Add to that the turnover caused by the MEP’s hiring and placement system, the learning process does not advance.”

Along these lines, we mentioned in the chat that during the pandemic, the MEP and public universities created a large number of new materials for teachers—but today, it seems that these aren’t being widely used.

Karla Rodríguez says: “But what if, for example, the resources generated by the MEP and the public universities were more organized and easy to access for everyone? Free resources, but more accessible.”

The State of Education research team agrees with Karla, stating that many resources do exist, but that it’s hard for teachers to lay their hands on the right tool at the right moment.

However, even with lots of resources, teachers agree that class time is one of the main enemies in this fight.

“I say this because it’s one of our biggest complaints” as English teachers, says Yessenia. “Perhaps it’s a justification for why students don’t speak English. There is no time. The curricula are extensive, and there is no time, and we are interrupted by thousands of other activities.

“It’s the same with reading,” Karla continues. “Many teachers would say that if you manage to complete the curricula, there is no time to pause and read. There is no time to plan, there is no time for the kids to analyze, comment, discuss, act”.

And teachers need—somehow, by some miracle—more time, too.

“Time to work on your ideas,” says Arturo. “And openness to do interdisciplinary projects. [Time for] dialogue with publishers, and to use technologies to bring young people closer to reading.”

Costa Rica needs a national campaign that promotes reading—for everyone’s sake.

So what do teachers need to promote reading in their classrooms? As you can see, we got many answers to that question in our Education 506 group. Reading corners and libraries in all schools. Time reserved exclusively for reading during Spanish class. More parent and family involvement. Greater use of multimedia tools. More time for interdisciplinary projects. More community spaces to read, write, create, and enjoy different media, such as the theater.

Throughout these brainstorming sessions, one idea kept coming up that goes beyond any individual classroom: a national campaign for reading. As we reported during “Let’s Read!”, this idea has been brought up by academics, but it also popped up during our teacher chats. Because teachers can’t do it alone. Nor can librarians, or even the MEP. Nor can parents—as the two of us, both mothers, have mentioned several times during this edition.

But the consequences of poor reading and critical thinking skills in the Costa Rican population will be experienced by all of us. They’ll take the form of chaotic elections, weakened institutions, more violent and less accurate public discourse, more limited employment opportunities. The list goes on.

What would such a national campaign look like, and how can it be accomplished? There the group participants, including us, were unsure. We are working our trenches—whether as teachers, parents, or journalists—with limited resources. It’s hard to imagine something so ambitious. But the idea hovered on the air, being mentioned at different times in our two months of conversation.

And you? Do you share that dream? Are you Interested in joining from your own trench—as an educator, business leader, academic, student, or parent?

Join the conversation here. Because for everyone’s sake, this is a conversation that needs to continue.

And that’s why, to everyone who participated in Education 506 this month, we offer thanks from the bottom of our hearts.

Meanwhile I was getting throught this passage, a couple of ideas or I should say shared concerns crossed my head. First of all, the extenssion of the curricula, there are many contents or themes which need to be covered per each level during the schooling year, it is incredible, if it’s possible to meassure those themes in terms of extenssion, perfectly it is possible to create a 50 pages book per week, where those topics are glutter and most of the time, senseless. Around the world, in the very competitive countries, a book, student’s and workbook relied on audio, videos, interactive plattform as a technological resource are used and have been proved to be efeective, obviously with correlated topics according to the country’ s culture. Besides, this really promotes reaserch through reading different material. But here in Costa Rica, if we go over the English curricula you can observe as a example, the present perfect tense is included such as grammar content in third grade when even not in their own mother tongue kids are able to understand. It is supposed that this syllaby is based on the MCER. The second point, it is the English time students are expossed is not enough, only 5 lessons per week for elementary school children have proved not be to sufficient to achieve the desaired proficiency competence level. Spanish subject has 10 lessons and eventhough students don’t develop good competences.