The final installment in a six-part series. Read Part I, “A harvest turned upside down,” Part II, “The 48-hour journey,” Part III, “Second home in a strange land,” Part IV, “Making ends meet,” and Part V, “The coffee dream.”

It is rare to feel a sense of awe when looking at a piece of paperwork. Wow, so that’s it. A real one. Right in front of me at last.

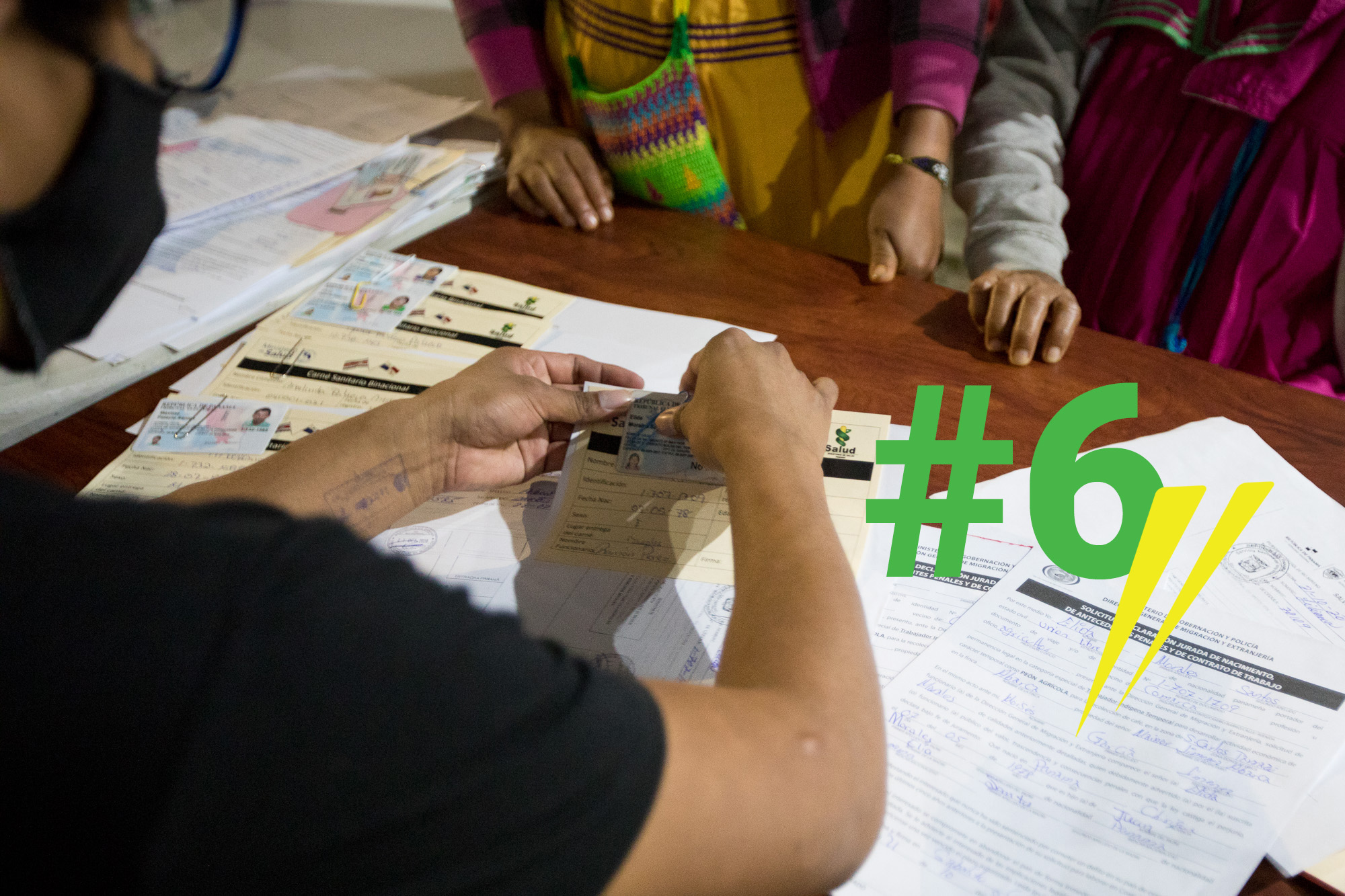

However, by the time we lay eyes on a carné binacional—the Costa Rican-Panamanian health card for migrant workers that was created out of the two countries’ need to find a way for Ngöbe-Buglé coffee pickers to cross a closed border during a pandemic—we’ve heard so much about it in conversation after conversation that it almost feels like meeting a celebrity.

The document is no miracle-worker. Take, for example, these cards that are laid out on a wooden bench inside Costa Rica’s immigration facility for a police officer to review. The family members who placed them there have been waiting 10 days at this border because Panama’s office is closed in the wake of Hurricane Eta, and Panamanian authorities want to disincentivize indigenous workers from heading to the border because of the heightened danger from rushing rivers and other threats. Indeed, this family has lost two children—two children—who were swept away during one river crossing. Those who were left behind, who continued their journey because there was nothing else to do, are furious, hungry, and grieving.

But because of these cards that lay out so carefully, they have a chance to do what they want to do, which is to work in Costa Rica and generate the savings they need to get through the rest of the year back in Panama. Because of these cards, according to health authorities, 6,510 Ngöbe-Buglé workers had crossed the border into Costa Rica by January 15th, the deadline for entry for the current harvest. Because of these cards, countless numbers of Costa Rican farmers snatched their harvest from what seemed, eight months ago or so, like a very real possibility of ruin.

The carné binacional, or Carné SITLAM (described in the Agriculture Ministry’s official COVID-19 protocol as the “personal identification document associated with the Migrant Labor Traceability System, SITLAM, which will allow for health monitoring and will have labor and migratory validity”) has been at the center of this year’s harvest. And as Costa Rica and its coffee industry looks forward to 2021, to a post-pandemic world, the card is at the center, too, of discussions about what lessons might endure.

Will Costa Rica’s newly heightened appreciation for its migrant coffee workforce disappear as soon as COVID-19 no longer lurks around every corner, making scrupulous health and safety provisions a necessity?

Will the relief that not only authorities, but also farmers and migrants, have expressed about 2020’s more orderly immigration oversight, be enough to ensure that such improvements are maintained or increased?

Will an industry facing threats not only from this year’s pandemic, but from coffee rust and other sources of financial strain, take advantage of technological tools that allow for greater traceability from branch to cup, and of workers from farm to farm?

Will improved communication among Costa Rica’s government entities, and among Costa Rica and its neighbors, be a flash in the pan, or will the people involved in this year’s migration make sure it continues?

Will these slips of cardstock on a bench become a memento of an unusual year, or the start of something more?

A long time coming

Dr. Christian Jiménez is quick to point out that this year’s coordination was not just a solution to the challenges posed by the global pandemic: it was also an answer to issues that had been attended to persistently, but perhaps not as effectively, for many years.

“The challenge began well before COVID,” says the director of the Public Health Ministry’s Director of the Brunca Region. “I’ve been working with this [indigenous border] population for 17 years, but historically, the Ministry of Public Health has been working with it since the 1970s, always in the border region.”

He explains that through Costa Rican-Panamanian treaties and other means, the two countries sought improvements to indigenous migrant health care, but the COVID-19 crisis kicked this into high gear. Even the binational card isn’t new: it just required pressure to become a functioning reality.

“There have been so many carnés,” he said, explaining that the ministry had tried to implement a longer document that even included the holders’ parents’ names. “With this one, we moved to a more basic card” that was much easier to put into practice. “It’s really focused. Does the person have a chronic illness? Does the person have COVID? Did the person arrive in Costa Rica in good health?”

Even this narrower focus resulted in long waits for the migrants who had to obtain the card and comply with requirements both in Panama and at the Costa Rican border station. As our reporting showed, even with an expedited process and the presence of Ngöbe-Buglé Cultural Advisors such as Deysi Jiménez to guide migrants through the process, families often waited four hours or more to complete the entire process and sometimes had to sleep at the border in order to finish their paperwork the following day. Still, the results were overwhelmingly positive in the eyes of health authorities.

“It has been a successful experience,” says Christian Valverde. “More than 6,500 indigenous people passed through Río Sereno, and none of the Ngöbes who entered the country were positive for COVID.”

Yandellin Sánchez, who works at the Río Sereno station with the nonprofit Hands for Health, notes that this stands in sharp contrast to the fears of some Costa Ricans before the migration began.

“Something very curious that’s left everyone talking is that… at the start, many people said, all those indigenous people are going to get us sick,” she says. “Everyone was so worried. And it was quite the opposite. Of all those 6,510 people who entered, they were all healthy, or at least asymptomatic. Those who were sick at Río Negro were because someone in Costa Rica made them sick.”

For Daguer Hernández, Sub-Director of the General Immigration Administration, the clearest sign of the document tracking system’s success is the fact that as the first Ngöbe-Buglé migrants finish their work in Costa Rica and begin to head back home, the government of Panama is accepting the holders the the binational card without a COVID-19 test, unlike other Panamanians who have to cross the border. It’s a show of confidence in Costa Rica’s pandemic handling inside the country as well as across borders, according to the official.

“The greatest success of this process has been the coordination between institutions that before, didn’t happen, or was minimal, and the coordination with the producer. This is a success we have to try to maintain,” he says. To place comments like these in context, it’s important to note the centralized nature of many Costa Rican institutions and the bureaucratic obstacles facing officials who try to work across institutions or even departments. It’s not unusual for an inter-institutional effort to require Cabinet negotiations or a formal agreement. And when it comes to the relationship between official counterparts in neighboring countries, smooth and constant communication, according to Hernández, was also much rarer before the pandemic.

“Our coordination with these countries [both Panama and, to the north, Nicaragua] and their authorities has allowed us to improve our overall migration relationships. They consult us, we consult them. We’re trying to carry out similar immigration policies so that we don’t affect the other country,” he adds.

At home in the fields

Positive impact from pandemic efforts went far beyond the border. According to Christian Valverde, part of the impact of this year’s harvest was that authorities in his institution and other parts of the government finally started to take a more integral approach to migrant health. Because adequate living conditions for migrant workers was essential to preventing and containing the spread of COVID-19 once the workers arrived, inspections at farms were an essential part of this year’s process.

Again, it’s been a long time coming. He still remembers the first time the Health Ministry closed a coffee farm in Coto Brus, 15 years ago.

“People were angry. Very angry,” he says, adding that “there was no water, the floors were dirty, the conditions unhealthy.” As international certifications for coffee farms such as the Rainforest Alliance became more common, the idea of improved living conditions for workers became more widely accepted, but again, the pandemic accelerated the process.

In both the regions explored for our series, we found and were told about farms where concrete floors had been poured, electricity provided, toilets built, and even new structures constructed. Of course, supervision and inspections were a key part of this process where resources allowed. Felix Monge, of the country’s largest cooperative, Coopetarrazú, said that the need to verify adequate living conditions at affiliate farms generated not only thousands of farm visits and monitoring of farms ordered to improve their conditions, but also a whole new level of technological traceability for the farming process.

“We can’t lie and say the region of Los Santos hasn’t lagged behind,” he says of worker living conditions. “The pandemic had to come and force us to be a little stronger.” He shows off the ARGIS control panel, based on the format that Johns Hopkins uses for COVID monitoring, that Coopetarrazú is now using to capture data about workforce needs, presence, living conditions and other data from its 5,000 affiliates. In Tarrazú, where many farmers work not with Pananamanians but with Nicaraguan migrants who this year were subject to an even stricter protocol—requiring farmers or, in the case of Coopetarrazú affiliates, the cooperative to coordinate and pay for their transport all the way from the southern Nicaraguan town of Rivas—this level of data management was essential.

It’s helped deal with “a long-time debt,” Felix says, and advocates of the indigenous community agree. Longtime International Organization for Migration (IOM) project leader Eduardo Navarro has worked with these issues for years.

“The social responsibility of employers is the great debt owed by Costa Rican coffee,” he says. “To this day, some employers don’t feel that responsibility for seeing the coffee picker as a person, as their equal when it comes to rights to have water, to have a bathroom.” But this year “the farm without housing, drinking water, a bathroom, the Health Ministry won’t give them a permit… And that will continue, because if they did it because of COVID, they are going to see that this gives them added merit when it’s time to sell their coffee.”

Improvements for the future

Both health and immigration authorities say that improvements will be made for the 2021-2022 harvest, and that efforts are already under way; specifics are not yet available, but given that the return of the migrants to Panama has not yet taken place and the future of COVID-19 in the region is completely uncertain, this should, perhaps, not come as a surprise.

Christian Valverde indicates that one change will be the addition of overall vaccine registry to the health card, so that the SITLAM system shows this information on each migrant worker. This will eliminate a significant and long-standing public health issue: the over-vaccination of migrants, particularly indigenous Panamanians who might not have a vaccination record. To be on the safe side, Costa Rican health authorities might vaccinate them on their way into the country during multiple years, or Panamanian authorities might do the same, exposing the migrant to an overload. He says authorities have considered biometric cards that would provide a full health history, but that this presents significant legal issues and is not an immediate likelihood.

For Daguer Hernández, at least three main action areas have emerged. One appears to take shape during the interview: when asked how the improvements in inter-institutional communications could be maintained, he muses over the idea, then says that a formal framework on the transit of migrant workers might do the trick. “Yes, I’m going to write this down right now,” he says, suiting the action to the words. “That’s the next step so that all this effort doesn’t come to nothing. Otherwise, another Executive Branch, another presidential administration, another Immigration Administration, and they want to start from scratch. Or next year, migrant labor won’t be so visible, because maybe in 2022 the COVID issue will have been resolved. The issue goes back under the table.”

He’s also going to be presenting the success of the binational identification card at a meeting of Central American immigration directors in February to seek the replication of 2020’s success throughout the region. A total of 42,000 migrants have crossed through Costa Rica since 2015 in hopes of making it across Central America and Mexico and into the United States; a common health tracking system would improve all countries’ efforts to deal with this constant flow, he said.

Finally, there’s the issue of enforcement. Farmers interviewed throughout the series indicated that they were seeing broad failures by other coffee producers to comply with protocols. In almost all cases, these same farmers recognized that this is partly because the government simply does not have enough resources to enforce compliance and inspect farms consistently.

The subdirector says that Immigration will be requesting 100 more police officers this year. The Immigration Administration has only three officers for all of Coto Brus, meaning that they must staff the busy border station and respond to any complaints coming in from the area’s 3,000 farms. Los Santos doesn’t even have an Immigration police unit, meaning that any complaint must be attended to by the 45 officers assigned to San José, up to two hours away.

A quick look at Costa Rica’s overall financial prospects suggests that relief for these challenges is unlikely to come anytime soon. It’s clear that to some degree, the future of the improvements of 2020 will depend on personal will. If the spread of disease on a coffee farm is no longer a direct and immediate threat to the industry and government institutions lack the resources to properly police all regulations, it will be up to individual farmers and to companies such as Coopetarrazú to keep things moving in the right direction.

Felix Monge says that anything less would be unacceptable.

“If COVID miraculously disappeared today, we are sure that having this guide to how our workers’ quarters really are, is something truly important,” he says. “It would be a mistake to go backwards.”

He says the same is true of the border processes.

“The main thing that should remain from all this is the will of the producers that the [immigration] process take place in an orderly manner,” he says. “It would be a great pity, a shame upon the coffee sector, if we can’t demonstrate the capacity to administer these processes well. An authority like ICAFE should keep pressuring the government and say, ‘We did it this way one year, and we must keep going.’”

Given that Costa Rica’s harvest depends on migrant workers, and poor conditions or border treatment is a constant threat to the sustainability of that workforce, this year’s improvements are nothing less essential for the industry, he argues: “This year we’ve fixed many issues that could be risks in the future.”

Edo Navarro says that despite all the challenges he’s seen, he’s optimistic for the permanence of this year’s changes, too. For him, the lasting impact of the Casas de la Alegría is the reason for hope.

“You should have seen what it took for us to get producers to understand their importance, to raise awareness about eliminating child labor,” he says of the daycare centers, which began in Coto Brus and spread north to Los Santos. Today, the program, which in Los Santos was spearheaded by Coopetarrazú, has become a widely recognized successful public-private partnership with permanent government support, and its supporters “boast about those centers… It’s a fixed cost, and it’s going to continue.”

One last look

As January draws to a close, Costa Rica, like most any country around the world, is a nation on the brink, looking forward, uncertain. Its first group of vaccine recipients, including the most vulnerable front-line health-care providers, have just received their second dose. The first Ngöbe-Buglé coffee workers to enter the country last year were becoming the first to exit back to Panama. Farms to the south, where coffee ripens first, are beginning to wrap up their harvests, while farms to Los Santos and points north are in full swing.

Deysi Jimenez Santo, the Costa Rican Ngöbe-Buglé woman who had so commanded the border station, mastering the complex border processes and shepherding indigenous families through long lines and paperwork, is back in her wooden house next to the Río Negro, the river that overflowed its banks during Hurricane Eta and swept part of her home away. She is out of work. Her position as a Cultural Advisor with the OIM ended in December; one of the advisors stayed on, handling the entire workload alone, with his position ending on Jan. 15 with the entry of the last migrants. She is caring for her children, awaiting the beginning of her last year of high school—which, after starting school for the first time at the age of 19, she is now going to finish this year. She sends a photo of last year’s grades, straight As, and says she wants to earn a degree in education with a focus on Ngöbe-Buglé culture.

Sergio Bejarano, according to his aunt, Maribel, is still at Finca La China. The lean young man whose fingers fumbled over the bandolas, or branches, on his first days picking coffee in early November is now an experienced picker. His wife has not joined him in Costa Rica. His three children await him back in Panama when the harvest ends.

The coffee farmers and administrators watch over their crops, measure their yields, manage the issues that come and go among their hard-working pickers. Marco Cerdas, Sergio’s boss at Finca La China, who believes so passionately in the power of the coffee industry as an equalizer, and frets over what he sees as a decline in the Costa Rican work ethic. Minor Jiménez at his fourth-generation operation in Los Santos, who takes a philosophical view of the symbiosis between farm owners and their indigenous or Nicaraguan workers. Isauro Abarca, who, from his pink house, surveys the farm he paid off through a year working as an undocumented worker in New Jersey as a young man. Maikol Valverde, at Coto Brus’s largest farm, Finca Río Negro, whose labyrinthine whiteboard that tracked the farm’s November COVID cases has been used more recently to track the coming and going of workers among farms.

Lucidia Hernández and her husband Minor Montero are doing the same thing on a smaller scale than Maikol, juggling and replacing and networking to keep their farm afloat as workers come and go. They’ve lost two additional workers to other farms since our last piece, but were able to replace them with Nicaraguan workers they had employed in previous years; the back-and-forth continues. They’re walking their fields and wondering when they will be able to resuscitate Tierra Amiga, their coffee-centered tourism microbusiness.

“Tourism is at zero,” says Lucidia, adding that they’ve started inviting neighbors in San Marcos de Tarrazú who are less familiar with the coffee industry to come and learn about the process.

And then there’s Máximo Palacios. He welcomes his journalistic pursuers with his typical amused grin when they arrive for their last visit, this time to the family’s home on Minor Jiménez’s farm. We come bearing gifts, but not the usual bags of rice and dried beans that we have used to offset any lost work time we cause workers by interviewing them as they pick. Instead, the bags we carry include the books Máximo asked for on our last visit, quietly but directly, for his daughters. (“I don’t know how to read myself,” he said as he stripped red beans from among the green, “but it’s important for them”). The girls take the bags and disappear into the room where the whole family sleeps on bunks. We can hear them laughing and chatting as they open the gifts and shuffle through their contents.

When they reappear, they try to look very serious. The eldest, Ílda, nods matter-of-factly when asked if the gifts were acceptable. Later, she’ll show off her incredible woven bags: her father’s has his name woven into the side. They pose for photos and gather around the camera to see the results. The rest of the time, they listen to their father, standing in their dresses, arms crossed.

Their mother, Élida, hangs back as always, a strong but silent presence as she keeps an eye on the beans that are burbling on the woodstove. The family has left their full sacks of beans a few yards up from the house to be measured, just around the curve, and during our conversation a Jiménez family truck comes and goes again after the daily medida.

It could be wishful thinking, just our imaginations, but it does seem that Máximo is slightly wistful as we prepare to head out for the last time. He asks when we’re coming back; when we respond that our reporting for this series is over, but that we hope to see him again someday, he considers this. “Maybe you’ll come to the comarca,” he says, referring to Panama’s indigenous territory and the home from which his family journeyed for 48 hours to reach this place. He’s told us with great pride about his wooden house high in the mountains of Bocas del Toro. It’s even colder there at night than here, he says now, gesturing out to the valley just beyond his home, obscured by thick clouds.

His final recommendation to us suggests a profoundly optimistic streak: despite the fact that he has seen us lose our footing on multiple occasions in the coffee fields as he leaps down precipices holding 50-kg sacks of cherries, he tells us that we should take a shortcut on our way back to our car. Rather than walking back that way we came in, he says that we should cut straight up to the main gravel road that leads to Alto San Juan.

“I’ll take you,” he offers. We look at the steep incline and shake our heads. “Well, I’ll walk you out the other way.”

Leaving behind the corrugated curves of his house—woodsmoke rising, dinner steaming, his daughter still talking animatedly inside—we make our way together through the twilight along the much flatter roadway we have chosen. The three of us pick our way across the shallow stream that cuts across the path.

When we reach the gravel road, we say goodbye, and then: “Maybe you’ll come to the comarca someday,” he says again. “You’ll ride horses.”

With that, he turns back. We lose sight of him quickly among the trees, his step light and sure as he vanishes into the gathering dusk.